Transformative Change Through Small Wins

September 2024

By Nikki Tierney, JD, LPC, LCADC, CPRS

NCAAR Policy Analyst

“Progress lies not in enhancing what is, but in advancing towards what will be.” -Khalil Gibran

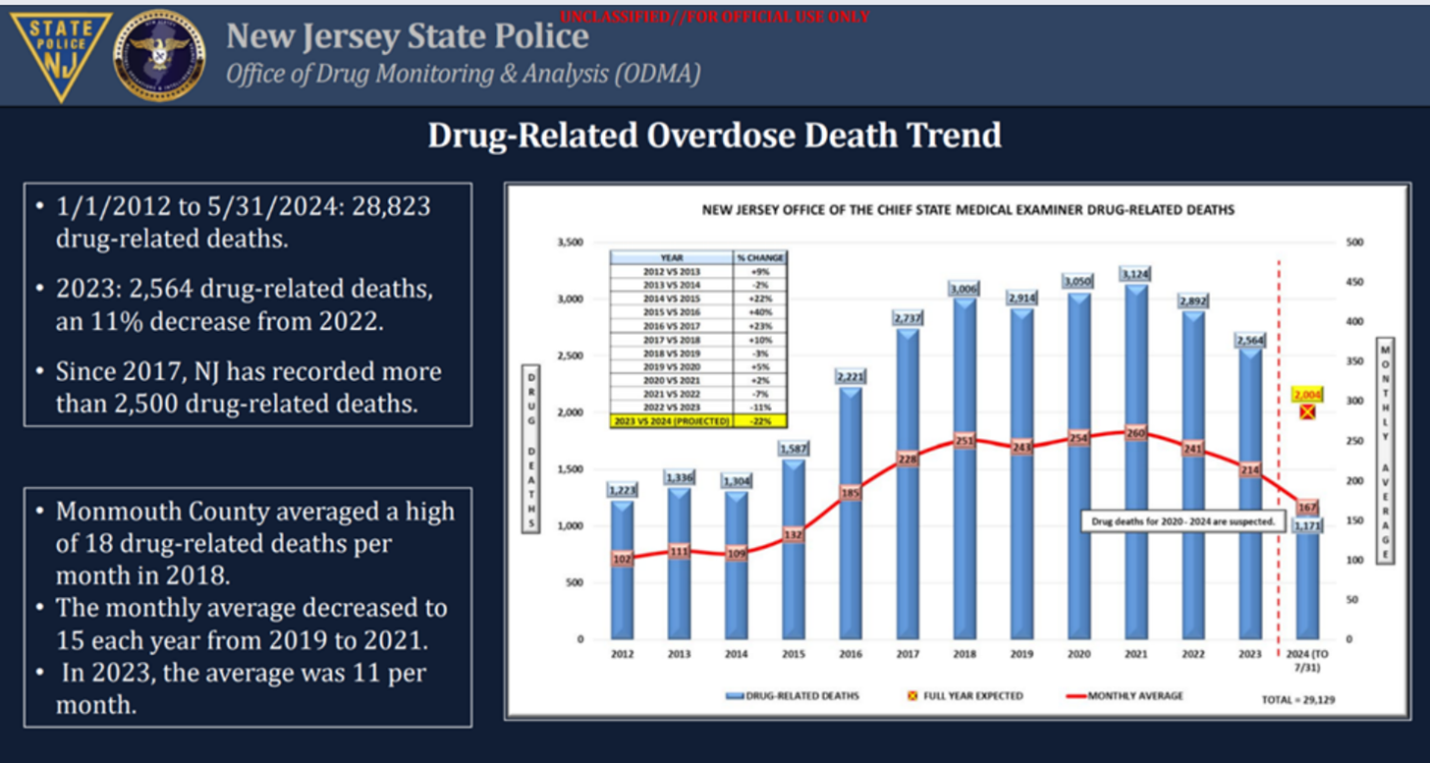

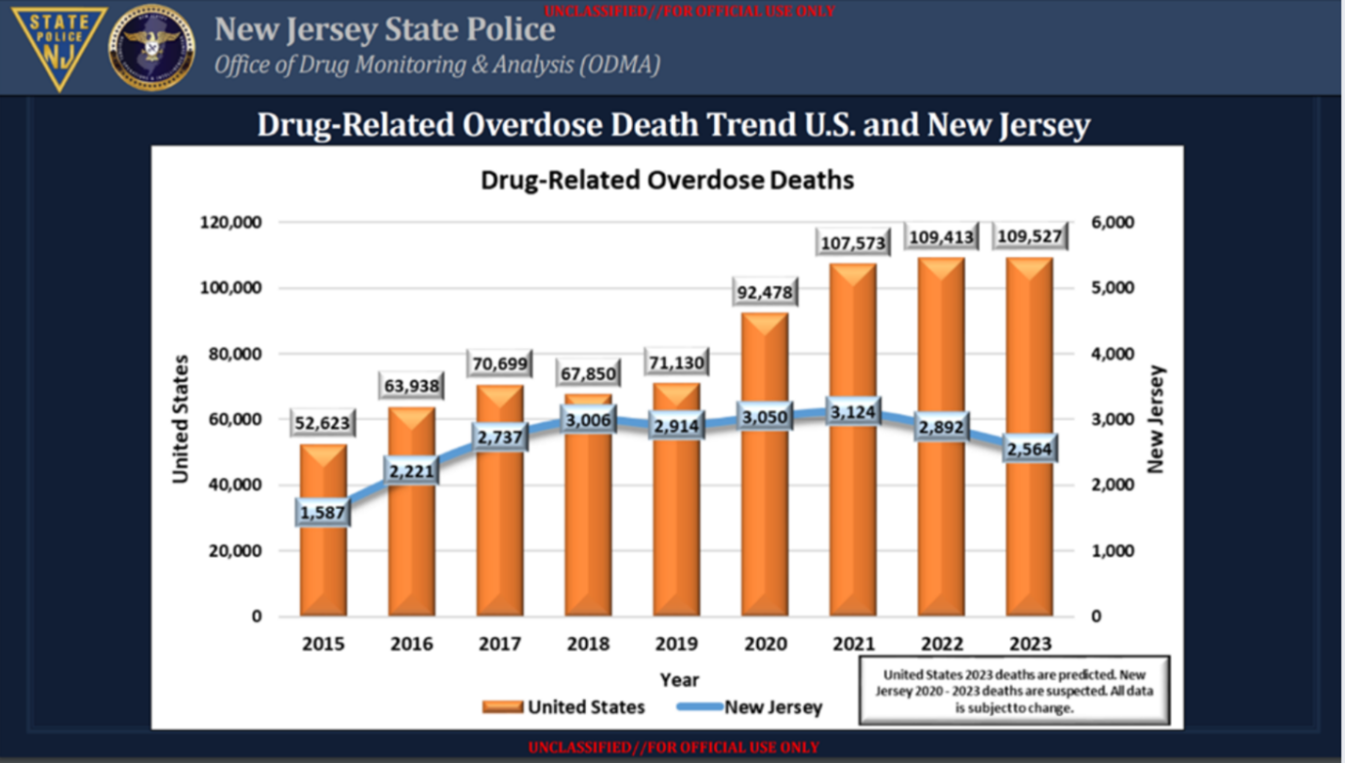

Over the past several years, there has been a change in New Jersey’s approach to the opioid epidemic. While NCAAR as an advocacy organization often brings attention to the barriers citizens face to access recovery, it is equally important to acknowledge the wave of positive steps the state has taken. Through various policy measures and programs, the state has demonstrated a new commitment to evidence-based public health responses to the drug epidemic, and those efforts are saving lives. During the first half of this year, drug-related deaths in New Jersey decreased by 26% and Camden County saw its drug-related deaths plummet by 39%, according to the Office of the Chief State Medical Examiner. In contrast, on a national level as of June 2024, drug related deaths are essentially the same as they were last year, according to the New Jersey Drug Monitoring Institute (see tables). 1  Even before this recent encouraging information, the CDC reported New Jersey’s decrease in drug-related deaths per capita improved drastically during the period of 2018 – 2023, improving at a greater pace than 20 other states in the nation. As Dr. Rahul Gupta, the Director of the White House’s Office of National Drug Policy explained, substance use disorder is a public health issue and its genesis is multifactorial, thus traditional cause and effect do not explain changes, but rather associations account for changes. 2 It is without question that New Jersey’s implementation of evidence-based principles, like harm reduction and improving access to treatment like medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD), are a part of the association resulting in lower deaths this year.

Even before this recent encouraging information, the CDC reported New Jersey’s decrease in drug-related deaths per capita improved drastically during the period of 2018 – 2023, improving at a greater pace than 20 other states in the nation. As Dr. Rahul Gupta, the Director of the White House’s Office of National Drug Policy explained, substance use disorder is a public health issue and its genesis is multifactorial, thus traditional cause and effect do not explain changes, but rather associations account for changes. 2 It is without question that New Jersey’s implementation of evidence-based principles, like harm reduction and improving access to treatment like medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD), are a part of the association resulting in lower deaths this year.

One of the most effective harm reduction tools New Jersey implemented has been ensuring that naloxone (trade name Narcan) is widely available and accessible.

Then, in 2022, New Jersey launched Naloxone Direct, which gives eligible agencies, including first responders, harm reduction agencies, county prosecutor’s offices, libraries and shelters the opportunity to request direct shipments of naloxone online at any time. More recently, the Department of Human Services and the Department of Education announced they are making naloxone accessible to all school districts at no cost through Naloxone Direct 4 In 2023, New Jersey increased access to this life-saving measure through its program, Naloxone365, which allows residents aged 14 and older to obtain naloxone without a prescription for free at participating pharmacies without providing a name or reason. A single two-dose naloxone nasal-spray kit is provided to each resident at their request. New Jersey is the first country in the nation to do so. To further access the program, New Jersey launched StopOverdoses.nj.gov, where residents can find pharmacies offering life-saving naloxone anonymously and at no cost.

Then, in response to the rapidly changing illicit drug market and the advent of xylazine, a non-opioid sedative, New Jersey leveraged policy changes to expand access to life-saving harm reduction supplies, including removing criminal penalties for all drug testing tools (fentanyl test strips and syringes were previously decriminalized in 2022). On January 8, 2024, Governor Murphy signed S3957 into law, expanding the definition of harm reduction supplies beyond syringes and removing criminal penalties for any materials or equipment used to prevent death, reduce the spread of disease, or reduce the adverse effects associated with the personal use of illicit substances. To further improve stigma-free access to Narcan and other harm reduction supplies, harm reduction kiosks/vending machines opened in Jersey City, Morris County, and Middlesex County this year, providing naloxone kits, training guides, first aid supplies, drug testing supplies, and more. Despite decades of research suggesting punitive approaches are ineffective and create more harm, legislation such as this would have been unheard of just a few years ago. It was a welcome and encouraging sign of shifting the focus from criminalizing and villainizing substance use to focusing on preventing unnecessary harm to the people and communities who are affected by such an approach.

In addition to legislative changes, New Jersey has designated additional funding through the recent influx of opioid settlement funds to support its new response effort. Harm reduction centers and services saw an increase in funding from $4.5 million to $16.5 million over the next two years, also drawing on opioid settlement funds. This builds upon legislation signed in 2021 by Governor Murphy that removed authority to approve or close syringe access programs from local municipalities, placing this authority with the Department of Health. This effectively removed some of the local restrictions on the operation of harm reduction centers to ensure they can continue providing critical care and services. With all these efforts and needed funding, New Jersey went from seven authorized harm reduction centers statewide to 49: twenty-three fixed sites, twenty-three mobile services, and three mail-based services. 5 Currently, thirty of these sites are operational.

Along with harm reduction centers, New Jersey has expanded access to MOUD by funding additional mobile medication units. Despite MOUD being a very successful and evidence-based way to treat opioid use disorder, these treatments are often underutilized by consumers due to being highly regulated and containing multiple barriers to access. Further, they are often under prescribed by physicians due to long-standing stigma against people with substance use disorders in the healthcare system. In 2019, in an effort to encourage more doctors to prescribe buprenorphine, New Jersey sponsored a buprenorphine training program with financial incentives for participation. 6 Unfortunately, a survey subsequently conducted revealed that out of 91 participants, only 73% completed the training and DEA registration requirements and a meager 34.8% were prescribing buprenorphine 4 months after the initial training.

Along with harm reduction centers, New Jersey has expanded access to MOUD by funding additional mobile medication units. Despite MOUD being a very successful and evidence-based way to treat opioid use disorder, these treatments are often underutilized by consumers due to being highly regulated and containing multiple barriers to access. Further, they are often under prescribed by physicians due to long-standing stigma against people with substance use disorders in the healthcare system. In 2019, in an effort to encourage more doctors to prescribe buprenorphine, New Jersey sponsored a buprenorphine training program with financial incentives for participation. 6 Unfortunately, a survey subsequently conducted revealed that out of 91 participants, only 73% completed the training and DEA registration requirements and a meager 34.8% were prescribing buprenorphine 4 months after the initial training.

Since then, however, the federal X-waiver requirement for prescribing buprenorphine has been rescinded and New Jersey is committed to expanding access to methadone. Assemblyman Moen, who was one of the proponents of a mobile methadone program by Sonara Health, explained “[m]ethadone is commonly referred to as “liquid handcuffs” among users because patients must go to the treatment centers to receive their daily dose of methadone. Requiring patients to go to treatment centers daily often conflicts with their jobs, family and personal life, and often results in less retention in treatment for OUD.” While this program did not contribute to the reduction in deaths this year, it is another example of New Jersey’s commitment to expanding access and improving the health outcomes of people who use drugs. Additionally, the State is reviewing the recent revisions made to Part 8 of Title 42 of the Code of Federal regulations (CFR) for Opioid Treatment Programs (OTP) which makes COVID-19 pandemic-related flexibilities for admission, take-home medicine, and other changes permanent. New Jersey’s adoption of these revisions would reduce barriers to accessing MOUD services, create a more individualized, person-centered service, and improve overall outcomes for clients. States were given an initial deadline for implementation of October 1, 2024, but many states, including New Jersey, are requesting additional time to review the sweeping changes.

A more recent study undertaken by Camden Opioid Research Initiative examined drug related deaths due to opioid-related drug toxicity in Camden or Gloucester Counties between March 2019 and April 2021. 7 The study examined demographic data as well as treatment and usage by each person who died, to identify barriers to treatment and common trends impacting risk for opioid use disorder. Just three (7%) of the samples showed evidence of MOUD, such as methadone or buprenorphine which may be attributed to the evidence that these medications prevent death from opioid toxicity when taken at the correct dosage. This study made helpful recommendations in guiding another response from New Jersey, demonstrating that one way to increase the use of MOUD is to introduce buprenorphine to ease withdrawal symptoms at the time of emergency response, immediately following the administration of naloxone. In 2019, the Department of Health authorized paramedics to carry buprenorphine and provide the medication to individuals who received an administration of naloxone. This measure not only provides a “soft landing” from opioid withdrawal symptoms, it also increases treatment retention rates.

New Jersey’s methodical approach to data and trends has resulted in the ability to target critical support through prevention, harm reduction, treatment, and wellness services and programs. In addition to the changes mentioned, New Jersey has integrated peer support specialists in the continuum of care, recovery support centers are open in nearly every county and receiving additional funding this year, MOUD services in jails and re-entry services expanded, people with lived and living experience have a seat at the table of the various state committees, the Overdose Prevention Act (a.k.a. Good Samaritan Law) was passed, and the “Anti-Stigma Bill” was passed in 2023, removing stigmatizing language concerning substance use from all New Jersey laws and state institutions.

New Jersey’s methodical approach to data and trends has resulted in the ability to target critical support through prevention, harm reduction, treatment, and wellness services and programs. In addition to the changes mentioned, New Jersey has integrated peer support specialists in the continuum of care, recovery support centers are open in nearly every county and receiving additional funding this year, MOUD services in jails and re-entry services expanded, people with lived and living experience have a seat at the table of the various state committees, the Overdose Prevention Act (a.k.a. Good Samaritan Law) was passed, and the “Anti-Stigma Bill” was passed in 2023, removing stigmatizing language concerning substance use from all New Jersey laws and state institutions.

There is a great deal of progress to celebrate and we must take the time to celebrate it. Dr. Daliah Heller, VP of Drug Use Initiatives at Vital Strategies, a global public health nonprofit organization who applauded New Jersey’s expansion of access to naloxone and MOUD and stressed that supervised consumption sites are another powerful evidence-based tool New Jersey should consider. 8 While it cannot be denied that New Jersey has taken robust action by integrating both data and policy to decrease drug-related deaths in the state, we undeniably have a long way to go. NCAAR, and the many other passionate organizations that dedicate themselves to changing the narrative around substance use, reducing stigma, and improving access to recovery know this is just the beginning. Changing long-held stigmatizing beliefs and how that manifests in policies and practices will take time, but we can all be encouraged by the state’s momentum toward evidence-based, lifesaving and life-enhancing interventions. Then, we keep advocating.

- According to preliminary data released by the CDC, between April 2023 and April 2024, nationwide overdoses decreased by approximately 10%.[↩]

- https://www.nytimes.com/2024/09/21/us/politics/drug-overdose-deaths-decrease.html[↩]

- Treitler, P. C., Gilmore Powell, K., Morton, C. M., Peterson, N. A., Hallcom, D., & Borys, S. (2022). Locational and Contextual Attributes of Opioid Overdoses in New Jersey. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 22(2), 108–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533256X.2021.1901203[↩]

- https://www.nj.gov/humanservices/news/pressreleases/2024/approved/20240913.shtml#:~:text=September%2013%2C%202024,Human%20Service’s%20Naloxone%20DIRECT%20program.[↩]

- https://www.nj.gov/health/hivstdtb/hrc/[↩]

- Nyaku, A. N., Zerbo, E. A., Chen, C., Milano, N., Johnston, B., Chadwick, R., Marcello, S., Baston, K., Haroz, R., & Crystal, S. (2024). A survey of barriers and facilitators to the adoption of buprenorphine prescribing after implementation of a New Jersey-wide incentivized DATA-2000 waiver training program. BMC Health Services Research, 24(1), 179. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-10648-2[↩]

- Kusic, D. M., Heil, J., Zajic, S., Brangan, A., Dairo, O., Heil, S., Feigin, G., Kacinko, S., Buono, R. J., Ferraro, T. N., Rafeq, R., Haroz, R., Baston, K., Bodofsky, E., Sabia, M., Salzman, M., Resch, A., Madzo, J., Scheinfeldt, L. B., et al. (2023). Postmortem toxicology findings from the Camden Opioid Research Initiative. Plos One, 18(11). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292674[↩]

- https://www.nj.com/opinion/2024/09/why-drug-overdose-deaths-are-dropping-fast-a-qa-with-dr-daliah-heller.html[↩]